The years have been good to the art fair, which celebrated its tenth anniversary this past weekend and staged its most inspired show to date.

The 10th edition of the Investec Cape Town Art Fair (ICTAF) took place last weekend on the southernmost tip of the continent where the black gold of the sun sets late and the ‘notion of time’ becomes an apt theme for Africa’s largest gathering of contemporary art. With over 106 exhibitors from across Africa and the diaspora, coming together for several panels and a number of exhibition openings across museums and galleries in Cape Town, the art fair made a generous space for an influx of devotees to reflect on disparate ideas of time itself.

Such was the collision of time and space for a Norwegian art fan, one of the 25,000 attendees, who, on the Friday of the art fair, found herself in the booth of South African artist Zandile Tshabalala’s solo show Umcimbi, standing on an earth-colored vinyl floor paper reminiscent of a childhood home in Soweto. The cake was frosted red, and shaped in the figure of 21, as an ode to the artist’s mother’s birthday — commemorating the universal” celebration of transition into adulthood. Tshabalala used this as a departure point to refigure ideas of gathering as a community in celebration of a Black femme’s growth and agency.

A fine-art painter with an affinity for prioritizing the rest and revelry of Black women, Tshabalala’s work, in conjunction with BKhz, was a portal into a contrast of colors that translated to a lush and insistent celebration of the self and one’s community. In the artist’s own words, her practice is an urgent and incessant response to the zeitgeist because, “that’s what we need, especially in painting history. We need a depiction of Black women in different angles, and not just this one story as it has been told throughout painting history.”

The mood reigned nostalgic in Tshabalala’s booth, where portraits of individual Black women were in conversation with scenes of family lunch being prepared in large pots. The most conspicuous paintings were those which placed the viewer in the position of a photographer gazing into intimate and celebratory family moments in the midst of a party, inviting attendees at ICTAF to recall their own birthday memories. What Tshabalala captured is the bold essence of cyclical body-time imprinted in sepia-tone film recollections and layers of paint, insisting that we “come party because hard times require furious dancing.”

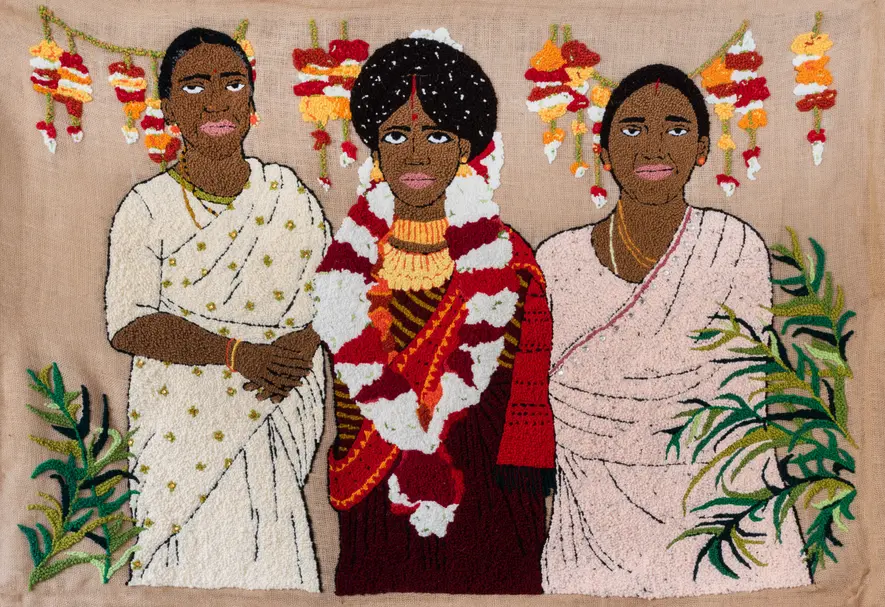

Weaving in and out of time to find herself a winner was fellow BKhz artist Talia Ramkilawan, whose striking textiles made of embroidered yarn conveyed a texture of time that is at once restless, provocative and serene. The South African Indian artist’s body of work Looking at the Same Moon blends still life and portraiture to such an exceptional degree that she was awarded the Tomorrows/Today Prize. A section of ICTAF tenderly brought to life by Natasha Becker and Mariella Franzoni, the Tomorrows/Today spotlighted 10 emerging artists.While co-curators Becker and Franzoni drew inspiration from Maya Angelou’s timeless poem In and Out of Time, Ramkilawan drew from the endless well of her hybrid identity. Marrying her unique existence and perspective of being Indian and a South African woman together with queerness, Ramkilawan told OkayAfrica, “Ultimately, I want my work to resonate with my people and my community, I want it to reach people that I know it will mean the most to.” On the hunt for serotonin and placing what she calls “Easter eggs of reality” in her artworks, Ramkilawan is interested in conveying both the vibrant colors of life and the reality of danger experienced by a woman living in South Africa.

Ramkilawan elaborates on her contemplative process of healing though making, expressing that “coming from a brown family, and an Indian family that was brought to South Africa as slaves, I am just trying to look at how we actively treat pleasure in our lives, and how that can happen through so many different forms, whether it’s through friendships, family, love, sex or just being alone.”

In as much as the Indian diaspora in South Africa produces creatives attuned to hybrid sensibilities, the continent and the Western diaspora is inherently marked by a sense of exile in reverse. For London-born multidisciplinary artist Shaquille-Aaron Keith, developing a relationship with what he calls “long-distance home” happened at an impeccable time.

Keith’s work on display with Eclectica Contemporary evoked traces of American artist Kerry James Marshall combined with measured reflections on childhood and projections of the self. A poem was etched in black on the white wall next to the mixed-media visual artwork I can’t hear you, It’s Picture day, almost as if the artist had torn a page out of his journal. The more comfortable Keith became in his craft, the more poetry became a medium to fill in the cracks in the imagery that depict the Black experience. As Keith says, “In each community you need people to speak about what’s going on in the community. I combine my real life and me observing with the surrealist part of my mind.”

It was Keith’s first time at the Cape Town Art Fair, and also his first time visiting the continent. He felt at ease, with cosmic kin orbiting him, attributed to his delicate balancing of the surreal and lived experience. Growing up in a musical household in South London, where his mother’s collection of instruments and art from her travels across different parts of Africa punctuated his growth as a creative, Keith always felt that he had to reconnect with where he is “originally from.”

Existing as a nexus for the diaspora both on and off the continent to connect through the visual arts produced in the present-day, this year’s ICTAF rippled sweet fate for Keith and Kenyan artist Nedia Were. Hailing from what Keith identifies as two different aspects of the global Black community, the two artists found alignment while exhibiting in the same gallery booth and set the intention to collaborate while they were both in Cape Town for the first time.

Coincidentally, Keith’s first set of oil paintings as a teenager were of the Masaai people of Kenya, who are indigenous to the Rift Valley region where the painter Were originates from, in Eldoret.

A self-taught artist who describes his process as “idea-based,” Were grew up entrenched in Western beauty standards in ’90s Kenya. As a creative consequence, the artist delves into questions surrounding identity, but also the canons of art education surrounding color theory. Gazing upon Were’s body of work, Mumwamu, which means “dark series” in his native language, it becomes apparent that the colors black and blue invoke an intentional move to embrace his community in his work, so that they feel seen and part of the conversation. His works are emotive, and as he tells OkayAfrica, they communicate that, “We are products of love, but things change along the way.”

Time itself is a concept that aligns for Keith and Were to meet in the middle ground, to explore simplicity, execution and synchronicity in a city which was seemingly waiting for them to collide. In the same way that time is the space where vulnerability and power can intertwine for Ramkilawan, nostalgia is the everlasting plane on which Tshabalala cordially invites us to celebrate free range of the mind and the infinite possibilities of our relationship to time.

This article was originally published by OkayAfrica