- The number of people displaced internally due to climate hazards could increase by more than 30% by 2050

- Our current approach to water management is insufficient and will likely exacerbate the effects of climate mobility

- Water resilience and social resilience should be integrated strategic priorities across sectors to mitigate the impacts of climate mobility

- Communities will “follow the water” which will drive scarcity and impact resource planning

Governments who fail to develop robust strategic responses to climate change and the water infrastructure crisis will increasingly find themselves at odds with their populations over the next two decades.

This disruption to the social contract between governments and citizens will go far beyond the service delivery and supply interruptions currently making news headlines. Rather this will fundamentally change where people choose to live, where they establish businesses and their willingness to invest in key economic sectors.

This is the view of Dean Muruven, Associate Director of Boston Consulting Group (BCG) who recently engaged media on a climate change roundtable.

“While there are some learnings from the loadshedding and energy crisis in South Africa – particularly when it comes to funding and Public-Private Partnerships – the water issue is far more complex,” explains Muruven adding: “Access to water is a basic human right enshrined in the South African constitution, this is not something which can be solved by simply increasing private sector participation.”

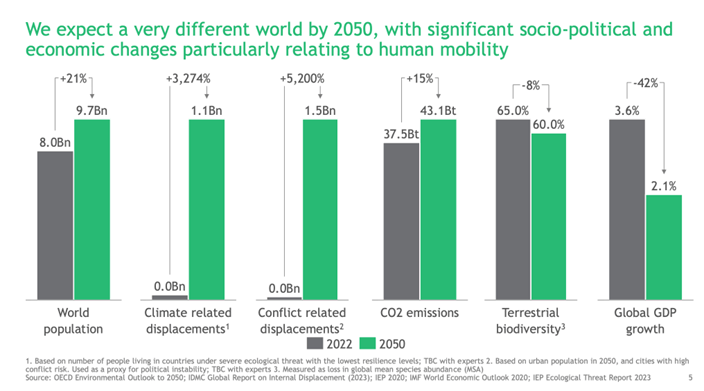

According to BCG research outlined in the To understand climate mobility, follow the water report, the number of people displaced internally due to climate hazards could increase by more than 30% by 2050 and thecurrent approach to water management is insufficient and will likely exacerbate the effects of climate mobility.

This is a particularly important challenge for Africa. The World Resources Institute released research looking at “National Water Stress Rankings” with 12 of the top 50 most water stressed countries on the continent.

In water scarce countries such as South Africa, this means that people will “follow the water” and this in turn will place additional constraints on water infrastructure while impacting town planning and resource management.

This is captured in the graph below:

“While the continent is broadly described as ‘water scarce’, Africa actually faces higher increases in climate mobility from flood risk, than drought risk by 2050,” explains Muruven pointing out that while the continent has made progress on energy security the crucial role of water in the food-energy-healthcare nexus has received little attention.

In Somalia for example, an extended drought has affected food security, exacerbating long-term displacement of the population while in Malawi the number of cholera cases has increased in flood affected areas. Analysis of migration data shows that there is a correlation between extreme floods in 2022 and the number of arrivals from Malawi into South Africa with two immigrants being identified as the original source of cholera coming into SA.

The floods in Kwa-Zulu Natal not only displaced people but resulted in significant infrastructure damage. This included R10bn in critical infrastructure, R400m in electricity transmission damage and disruptions to oil and coal supply lines coupled with job losses.

Gauteng is the economic hub of South Africa and loses over 40% of its piped water to leaks and illegal connections and ultimately impacts revenue collection for municipalities. There are estimates from economists that if Gauteng were to reach its “Day Zero”, the economic cost could be as much as R3bn per day in lost business activity.

Muruven concludes: “While we are framing this discussion around 2050, stakeholders from government to the private sector need to understand that this is an issue which is having a direct impact here-and-now and the challenges will only get greater, the longer we delay in developing robust, strategic long-term plans.”